Three trees

There are a few JVM based languages that I either have been using on and off, or curious to know about. So I decided to cover them in an article where I implement the tree based algorithm already covered in the previous articles on Scala3, various versions of Java and Rust.

This time I decided to cover:

Groovy

Groovy is one of the first JVM based languages, and thanks to its use as Jenkins DSL, it has been quickly adopted. I have used it occasionally over the years but mostly as Jenkins DSL and also when writing Gradle build scripts.

I thought that would be interesting to do something a little more complicated with it. The first impression is, that despite having some functional elements like Closures, the lack of modern functional constructs like ADT makes the language feel a bit outdated.

Actually modelling the tree, the most idiomatic design seem to use inheritance (similar to the design with Java 6):

interface Tree<T> {

Tuple2<Tree<Tuple2<T,Integer>>,Integer> addId(Integer index);

}

One advantage of Groovy is that types are already available for tuples which allows for a more elegant implementation.

Another nice extension of Groovy is the @Immutable notation with which the implementation of ‘‘hashCode()’’ and ‘‘equals()’’ are automatically added.

@Immutable

class Leaf<T> implements Tree<T> {

Tuple2<Tree<Tuple2>, Integer> addId(Integer index) {

return new Tuple2<Tree<Tuple2>, Integer>(this,index)

}

}

Still for the Node implementation we cannot use @Immutable because all class variables also need to be immutable.

So here we have to implement equals. hashCode is not implemented as it is not necessary for that example.

It is also worth noticing that as Groovy is an interpreted language, it took me a few runs to get all types ironed out, some of the errors would have been caught by a compiler with a fully static typed language.

class Node<T> implements Tree<T> {

final private T value

final private Tree<T> left

final private Tree<T> right

Node(T value, Tree left, Tree right) {

this.value = value

this.left = left

this.right = right

}

@Override

boolean equals(o) {

if (this.is(o)) return true

if (getClass() != o.class) return false

def node = (Node<T>) o

this.value == node.value && left == node.left && right == node.right

}

@Override

Tuple2<Tree<Tuple2<T, Integer>>, Integer> addId(Integer index) {

Tuple2<Tree<Tuple2<T,Integer>>,Integer> newLeft = left.addId(index)

Tuple2<Tree<Tuple2<T,Integer>>,Integer> newRight = right.addId(newLeft.second)

return new Tuple2<>(

new Node(new Tuple2<T, Integer>(value, newRight.second),

newLeft.first,

newRight.first),

newRight.second + 1)

}

}

Another nice feature of Groovy is that it is quite lax with semi-columns making the code easier to read.

All in all, Groovy is a good super Java and very powerful to implement DSLs. Surprisingly enough, Groovy is still evolving. Version 4, incubating at the time of writing has ‘records’ and an improved ‘switch’.

Because of its extensive use in Jenkins and as a glue language, there is a lot of existing code but most of it does not use any of the advanced features.

Kotlin

With Scala and Java experience, Kotlin feels very familiar. Coming from Scala, which thanks to Martin Odersky, has very solid theoretical foundation, I was expecting a more ad-hoc feeling like with Kotlin.

Let’s see if my preconceptions are confirmed.

To model the tree, ADT support is good and the language has immutable structures so no need to implement equals/hashcode:

sealed class Node<T> {

data class Leaf<T>(val dummy: Int) : Node<T>() // Cannot use object there because of generic

// and dataclass has to have a value

data class Branch<T>(

val v: T,

val left: Node<T>,

val right: Node<T>

) : Node<T>()

}

One limitation compared to Scala is that ‘object’ cannot be used with ‘generics’.

So although we need only one instance of ‘Leaf’, to make it compile we need to add a dummy parameter to make it a class. Clearly here Scala is a lot better thought out. That is an edge case but usually it is where the complexity lies, it is the last 20% that takes 80% of the time to implement. The implementation in Scala 3 is really neat in comparison.

Pattern matching, although not as extensive as in Scala is still well thought out. In the expression after the is, it is possible to directly access the fields of the type: for example although tree has type Node<T>, in the Branch expression we can use tree.left, tree.right and tree.v.

Tuple support is good but a bit verbose in my opinion.

fun <T> addId(tree: Node<T>, index: Int): Pair<Node<Pair<T, Int>>,Int> {

return when (tree) {

is Leaf -> Pair(Leaf<Pair<T, Int>>(0), index)

is Branch -> {

val newLeft = addId<T>(tree.left, index)

val newValue = Pair(tree.v, newLeft.second)

val newRight = addId(tree.right, newLeft.second+1)

Pair(Branch(newValue, newLeft.first, newRight.first), newRight.second)

}

}

So Kotlin is clearly more than another super java, and as you would expect, it has great support in Intellij. For other languages, especially on small projects, I prefer to use VS Code, there is just less fan noise from the laptop with it ;-).

All in all, Kotlin is a good language, more concise and more pleasant to use than Java in my opinion but not as finished and thought out as Scala, especially Scala 3.

Clojure

I decided to add Clojure to the list as I thought it would be fun and I was thinking maybe I could use it for the advent of code as well.

For the record, I really looked at Clojure in 2011 when I bought the first edition of Programming Clojure. I have been knowing about Lisp and Scheme before but that was the first time I really properly learned one language of this family.

I wrote a few test/glue programs with it. I also learnt Scala at the same time and knowing both was really helped me understand the specificities of functional programming.

First, let’s state the obvious, although Clojure runs on the JVM the code clearly does not look like Java !

It still shares some common ancestry with Java, as Java itself has inherited quite a few concepts from Common Lisp like the optimized virtual machine and extensive common libraries (as well as Object Orientation to add a bad inheritance pun ;-) ). Although to be complete, the lineage is probably indirect as the designers of Java probably have looked to SmallTalk which itself took a lot of inspiration from Common-Lisp.

So to go back to our algorithm, modelling the tree is very straight-forward, nested lists all the way !

(def tree '("a" ("b") ("c" ("d") ("e"))))

As Clojure is not statically typed, I present an instance of a specific tree. There is an extension to add type notation to Clojure, Typed Clojure but it is not part of the core Clojure language.

To add the 'id' to the note, I simply replace the value by a list with 2 elements, the first one being the value and the second the identifier.

Here is the code for the function to add the identifier:

(defn addId

"Add unique id to nodes in a binary tree"

[tree i]

(case (count tree)

0 tree

1 (list (list (list (first tree) i)) (+ i 1))

2 (let [

nvalue (list (first tree) i)

left (addId (first (rest tree)) (+ i 1))

]

(list (list nvalue (first left)) (first (rest left)) ))

3 (let [

nvalue (list (first tree) i)

left (addId (first (rest tree)) (+ i 1))

right (addId (first (rest (rest tree))) (first (rest left)))

]

(list (list nvalue (first left) (first right)) (first (rest right)) ))

)

)

Interestingly enough, as I was a bit rusty with Clojure I used a TDD approach to get it right as I couldn’t use the type system as crutches for my failing memory ;-).

I also used more intermediary variables compared with the implementation in other languages as I was not used to read expressions with a lot (too many ? ;-)) parenthesis. Having to use a list to store tuples also makes the code less readable and more verbose.

While thinking of how I could make the implementation a bit more DRY as the code for the right and left branch is very similar, I realized I could simply use a fold on the list of sub trees and generalize the implementation from a binary tree to an n-ary tree.

Again I used unit tests to get all cases right.

The implementation ends up being not much longer than the previous one, quite readable, and without duplicating code:

(defn addId-nary

"Add unique id to nodes in an n-ary tree"

[tree i]

(case (count tree)

0 tree

(let [

nValue (list (first tree) i)

branches (rest tree)

reducef (fn

([] (list (+ i 1)))

([a tree]

(let [

nTree (addId-nary tree (first a))

] (cons (first (rest nTree)) (cons (first nTree) (rest a)))

)

)

)

n-branches (r/fold reducef (rest tree))

] (list (cons nValue (rest n-branches)) (first n-branches)))

)

)

Out of curiosity I also tried to store the list in a hash-map to see if the implementation would be more readable:

(defn addId-hm

"Add unique id to nodes in a tree store in a hash-map"

[tree i]

(if-not tree (list '() i)

(let [

nValue (list (tree :value) i) ;; we do not handle missing :value

left (addId-hm (tree :left) (+ i 1))

n-left (first left)

i2 (first (rest left))

right (addId-hm (tree :right) i2)

n-right (first right)

i3 (first (rest right))

r {:value nValue}

r2 (if (empty? n-left) r (assoc r :left n-left))

r3 (if (empty? n-right) r2 (assoc r2 :right n-right))

] (list r3 i3))

))

There is a little less of ‘list wrangling’ but still a fair share of duplicated code.

Conclusion

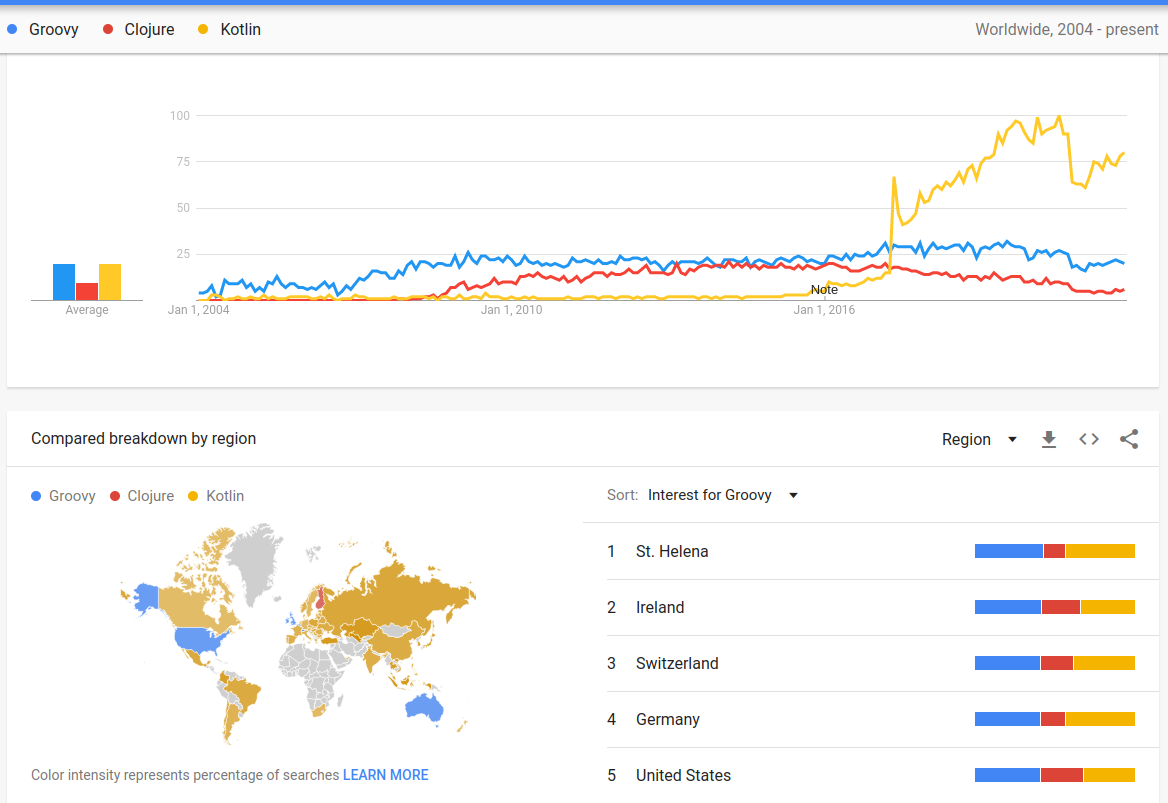

Out of curiosity I checked Google trends for all three languages on Tuesday 2 November 2021 and here are the results:

As expected Groovy has been the longest around and interest seems fairly constant.

Clojure started to get visibility end of 2008, plateaued until beginning of 2017 and then has been going down since.Hopefully that’s not related to the fact that it has been used by an infamous British tabloid based in High Street Kensington.

Kotlin success has been a lot faster, interest started to show beginning of 2015 (the first version was released in July 2011) but interest really shot up when Google announced the support of Kotlin in Android Studio 3 in 2017. Since then interest has been quite high.

From a geographical perspective, I was surprised to discover that:

- Groovy is the most popular of the three in the US, Australia, Ireland and the UK.

- The only ‘Clojure’ majority area is Finland. As you would expect you can find some discussions on why in reddit which point to this presentation.

- Kotlin dominates the rest of the world.

As a conclusion, Kotlin may succeed as a general purpose language as it clearly is more than a super Java. In my opinion Scala is superior in term of expressivity and consistency but as Kotlin has excellent tooling and the support of Google via Android, that may tip the balance in its favour.

Groovy has found its niche as a very capable DSL and is likely to stay around for some time.

Clojure is the most interesting language of the three because of its inheritance and idiosyncrasies. I have used it a glue/quick prototyping language where it really excels.

Clojure is also a great language to learn to deepen our knowledge but it may not be a great choice for long lived projects which see team turnover. First, even for engineers who know it, for a project that contains other languages it requires some mental gymnastic when switching. Also it will take more time for an engineer to get fully up to speed on the project if some parts are in Clojure. It clearly makes it harder to recruit but on the other hand, people who know Clojure may be of a higher calibre than engineers than only know Java.

Realistically, for new projects if I need a glue/prototyping language, I would now use Python as it is widely available and the syntax doesn’t scare most people ;-).